Published on the LSE USAPP blog on 31 October 2019

In a highly polarized political environment, it is not surprising that even basic democratic institutions become a matter of partisan conflict. The Federal Government of the United States is no exception in this respect. As research shows, partisans trust the government more when their party controls the Congress or the presidency. Yet, it seems that it is mostly conservatives and Republicans that strongly derive their support for the federal government depending on who sits in the Oval office.

In a recent research with John Jost and Vishal Singh, we find that in the United States, conservatives trust the government more than liberals when the president in office shares their own ideology. Furthermore, liberals are more willing to grant legitimacy to democratic governments led by conservatives than vice versa. A similar difference applies to Republicans compared to Democrats. This is what we call an “asymmetrical president-in-power effect”, namely that support for the government fluctuates more among conservatives and Republicans than liberals and Democrats depending on who is in the White House, in line with recent commentary.

A time trend

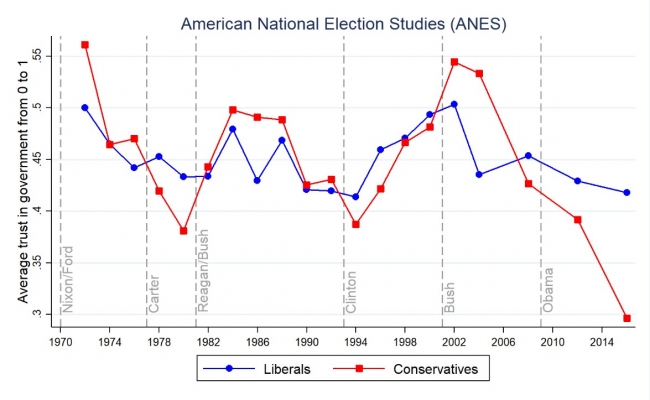

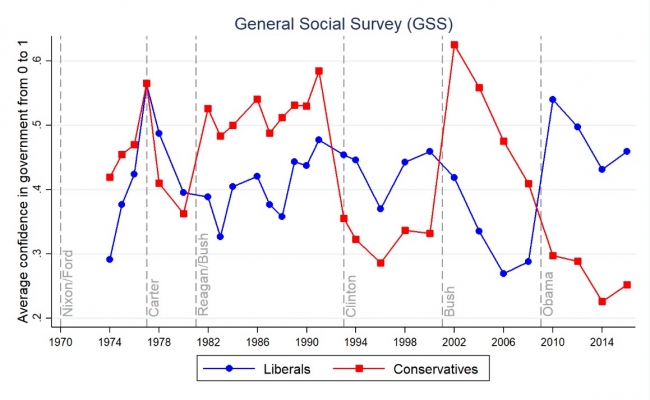

To identify the president-in-power effect on trust in the government we analyzed many surveys conducted by the American National Election Study (ANES) and the General Social Survey (GSS) since the early 1970s. Every second or fourth year the ANES has asked Americans “How much do you trust the Federal Government to do what is right?”. Similarly, GSS surveys routinely included a question on how much confidence Americans had in the executive branch of the federal government.

“Presidential podium” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Figure 1 shows a simple trend of how trust in the government changed since the early 1970s based on ANES data, while Figure 2 shows the same trend based on GSS data. Despite fluctuation over time, data from both ANES and GSS indicate that the major source of variation in trust in the government is on the conservative side, whereas confidence in the government among liberals does not vary systematically as a function of the president in power. In addition, historical trends suggest that the trust gap between liberals and conservatives widened slightly over the last two decades. When we replace ideology with partisanship, we find an even starker contrast between Democrats and Republicans.

Figure 1 – Trust in the government by ideology (ANES)

Source: Morisi, Jost, and Singh (2019)

Figure 2 – Trust in the government by ideology (GSS)

Source: Morisi, Jost, and Singh (2019)

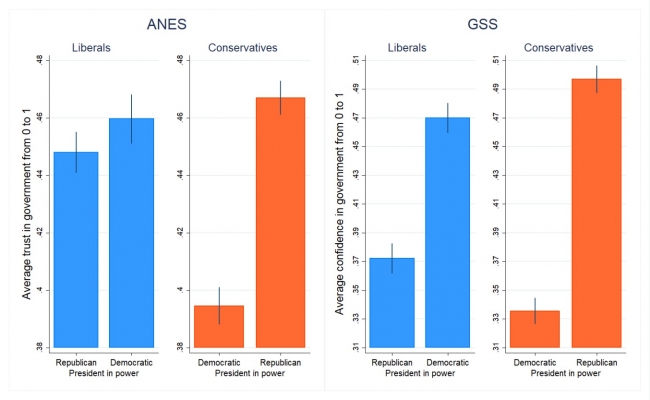

To calculate the president-in-power effect on trust we pooled all the available surveys from ANES and GSS from the 1970s to 2016 and conducted a series of multivariate regression models. Figure 3 summarizes the results. As the bar graphs clearly show, both liberals and conservatives trust the government more when the president shares their “own ideology” (i.e., a Democratic president for liberals, and a Republican president for conservatives). However, the president-in-power effect is clearly larger for conservatives compared to liberals.

The ANES data shows that conservatives trust the government seven-percentage points more under a likeminded president (versus a not like-minded president), whereas the increase among liberals is only of one percentage point. In GSS data, conservatives’ confidence in the government increases by 16-percentage points under a like-minded president, whereas liberals’ confidence increases only by 10-percentage points. A similar asymmetrical president-in-power effect occurs between Republicans and Democrats.

Figure 3 – President-in-power effects on trust in the government by ideology

Source: Morisi, Jost, and Singh (2019). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals

When we replicated the analysis using an additional dataset from the PEW Research Center throughout the period 2006–2017 we found a similar trend also in relation to the most recent change of presidency. That is, conservatives and Republicans exhibited a stronger tendency to trust the government more under a Trump (vs. Obama) presidency in comparison with liberals’ and Democrats’ tendency to trust the government more under an Obama (vs. Trump) presidency.

Why an asymmetrical effect?

We believe that two major factors can explain such a difference between conservatives and liberals. These reasons are far from mutually exclusive, but, on the contrary, we suspect that they work together in tandem. The first one is the fact that Republican elites have become ideologically extreme. Although elite polarization is a matter of debate, evidence shows that “Republicans in Congress have moved further to the right than Democrats have to the left over the last 40 years”. There is also evidence that the Republican Party has become more ideologically intense than the Democratic Party.

The second reason pertains to psychological differences between liberals and conservatives. A recent review of more than 180 studies reveals that, in comparison with liberals, conservatives have higher motives to share a sense of reality with like-minded others. If citizens regard domestic politics as a form of in-group/out-group competition, it follows that conservatives would exhibit more loyalty when it comes to supporting government run by their own “side,” and to exhibit more distrust when it comes to government run by the other “side.”

Our findings raise several theoretical and practical questions about democratic functioning. How is it possible to guarantee democratic stability if trust in the government shifts substantially as a reaction to the chief executive in power? Do governments under Republican presidents have a disproportional advantage, due to liberals’ tendency to trust the government from the other side more than what conservatives do? Lastly, it is worth considering whether “corrective” measures exist to upend the tendency we have identified. If politicians were to promote a less adversarial environment and to frame politics less in terms of intergroup conflict, would citizens be more willing to trust a democratically elected government with a decidedly different point of view?

- This article is based on the paper, ‘An Asymmetrical “President-in-Power” Effect’ in American Political Science Review.